“In this age of technology where you can simulate or manipulate anything, how do we retain that human element?”

– Dave Grohl in “Sound City”

There’s no understating Kurt Cobain’s role in the musical paradigm shift that Nirvana initiated with “Smells Like Teen Spirit,” but sonically speaking, it’s Dave Grohl’s monstrous four-beat drum intro that kickstarted the revolution.

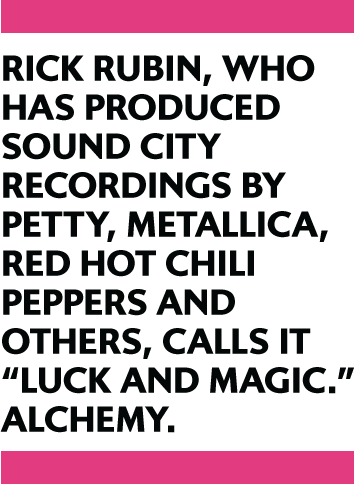

Drums play a starring role in the legend of Sound City, the famed studio where “Nevermind” and more than a hundred other gold- and platinum-selling albums were recorded. In Grohl’s “Sound City” documentary, he’s one of several musicians, producers and recording engineers who wax philosophic on the rhythmic alchemy witnessed inside this unassuming studio on the outskirts of Los Angeles. Yet pinpointing what, exactly, is responsible for the “Sound City drum sound” eludes them all.

Sound City Studios opened in 1969. Its original owners, investors Joe Gottfried and Tom Skeeter, were new to the music industry. Admittedly, they were only in it for the money. And it showed. The ramshackle studio, located in an aging business park in the patently unsexy neighborhood of Van Nuys, was behind the times and, figuratively and literally, outside the L.A. fast lane. Business went more thud than boom. But rather than cut their losses and move on to other ventures, Skeeter dug in and purchased a colossal state-of-the-art recording console — one of four in existence – recently developed by British electronics engineer Rupert Neve. The price tag was $75,000, more than double that of Skeeter’s latest home purchase.

Credit the analog Neve 8028 console – “The Facilitator” as it’s referred to in Grohl’s documentary – for transforming Sound City from a floundering upstart into L.A.’s hottest studio, with the likes of Fleetwood Mac, Tom Petty, and the Grateful Dead flocking there to cut records in the 1970s. But the building itself deserves some credit, too. When the Neve arrived, a symbiotic relationship quickly developed. Rock music, as filtered through the Neve, comprehensively rocked inside the former warehouse’s crumbling walls, particularly the drums, the instrument most impacted by the environment surrounding it.

Yet even Sound City’s reputation as one of those rare-air studios with an intangible “feel” could not protect it from the march of progress. When digital technology started infiltrating music-making and studio recording in the 1980s, the all-analog Sound City once again struggled. But then in 1991, three underground musicians from Seattle with a new major-label recording contract trekked down the coast to Sound City for a 16-day session. Nirvana chose the studio more for its affordability than its reputation, but the Neve board was a key selling point. No one at the time had any inclination of the impact “Smells Like Teen Spirit” would have on the music industry, but the session ultimately provided a boon for Sound City. Once Nirvana broke, everyone wanted to record there. Albums by Blind Melon, Rage Against the Machine, Tool and Rancid, among others, followed in the footsteps of “Nevermind.”

Yet even Sound City’s reputation as one of those rare-air studios with an intangible “feel” could not protect it from the march of progress. When digital technology started infiltrating music-making and studio recording in the 1980s, the all-analog Sound City once again struggled. But then in 1991, three underground musicians from Seattle with a new major-label recording contract trekked down the coast to Sound City for a 16-day session. Nirvana chose the studio more for its affordability than its reputation, but the Neve board was a key selling point. No one at the time had any inclination of the impact “Smells Like Teen Spirit” would have on the music industry, but the session ultimately provided a boon for Sound City. Once Nirvana broke, everyone wanted to record there. Albums by Blind Melon, Rage Against the Machine, Tool and Rancid, among others, followed in the footsteps of “Nevermind.”

But then, Pro Tools. By the late ’90s, the digital recording software had improved enough to be taken seriously by professionals, and the music industry was seriously into it. Musicians could now make albums in their bedrooms. Producers and engineers could mix and edit in a fraction of the time. Record labels no longer had to front six-figure studio budgets. The traditional recording studio suddenly seemed like a quaint, archaic notion, and several studios disappeared. The casualties included Sound City, which, despite selling off equipment in an attempt to stay afloat (Grohl himself bought the Neve console), closed its doors to the public in 2011.

Two years later, Grohl’s “Sound City” documentary hit theaters. Analog was already in revival mode thanks to the vinyl resurgence and the back-to-basics ethos of labels like Jack White’s Third Man Records and Brooklyn’s Daptone Records, but Grohl’s film spurred renewed interest in the old-school, put-everyone-in-the-same-room recording studio. This led to a reopening of Sound City in 2016 by Skeeter’s daughter Sandy (Tom passed away in 2014, Gottfried in 1992). While this new version of the studio includes a Pro Tools rig, vintage analog gear still provides the framework, and the main studio looks the same as it did in 1969 – all the way down to the peeling paint and cracked linoleum that remains for fear of altering the space and losing its signature sound.

Analog isn’t easy. It’s painstaking work, and when a mistake is made, a computer can’t repair it with a few clicks of a mouse. Sometimes being disruptive means resisting innovation rather than embracing it, and Sound City’s second life is proof of that. In his film, Grohl concludes that Sound City “represents integrity.” In the 21st century, the studio has found a way to use technology as a tool while staying true to its analog roots and retaining its mystique. When the creator and the consumer demand authenticity, that’s the symbiotic space where a challenger brand can make its mark.

______

SOURCES:

Sound City, directed by Dave Grohl, January 31, 2013

http://www.soundcitymovie.com

Q&A: Dave Grohl on His Sound City Doc and Taking Risks in Music, by Katie Van Syckle, Rolling Stone, January 25, 2013

https://www.rollingstone.com/movies/movie-news/qa-dave-grohl-on-his-sound-city-doc-and-taking-risks-in-music-242976/

L.A. Grapevine, March 2009, by Bud Scoppa, Mix, March 1, 2009

https://www.mixonline.com/recording/la-grapevine-march-2009-367413